The ‘Land-Bridge’: Henry Carey’s Global Development Program

Product Information

by Anton Chaitkin

Nearly a century ago, the British Empire dragged humanity into World War I to stop just such a cooperative development; they later boosted Hitler into power in Germany, looking forward to another great war, for similar reasons.

The earlier “land-bridge ” efforts, which we describe in this Feature, were launched following the Civil War by economist Henry C. Carey and Americans under his leadership. During the next decades, these nationalists and their international associates worked to make Germany, Russia, China, Japan, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, and other countries into modern, powerful nation-states.

The following were among the particular goals of this initiative:

• Making Germany a superpower and America’s partner in world development;

• Industrialization of Russia and China, with thousands of miles of rail lines;

• Development of Japan as an industrial power and counterweight to British genocidal Asia policies;

• World-wide electrification;

• The upgrading of labor and the condition of the people, as a necessary precondition for this industrial development.

And in order to succeed in these global purposes, the Carey circle planned an Irish uprising and the arming of Russia for a joint U.S.-Russian war effort to destroy the British Empire.

The planners of this world development crusade, who had sponsored President Abraham Lincoln, were the established leaders of America’s industrial, military, scientific, and political life. Yet, by around 1902, British-allied financiers had displaced these nationalists from power, and their way of thinking-the heritage of the American Revolution-had become a fading national memory. Under Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, the mighty U.S.A. functioned in most respects merely as a British

pawn.

Thus by 1905- 14, the main players on the world stage, such as in Russia, China, Japan, and Germany, operated in the desperate circumstances that the actual American republic, which had fought powerfully for the successful development of their nations, had, in effect, disappeared as an independent factor in world affairs.

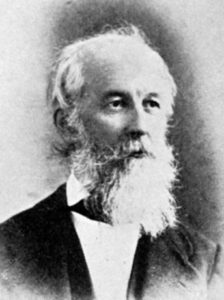

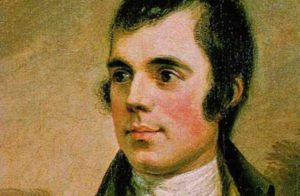

Henry Carey (1793- 1 879) was probably the world’s most famous living economist during the 1860s and 1870s. Carey’s books and pamphlets were translated into most major languages, forming, with his predecessors Friedrich List, Henry Clay, and Alexander Hamilton, the main representation of the American or national school of political economy, opposing the British imperial school represented in print by John Stuart Mill and earlier writers such as Thomas Malthus, David Ricardo, and Adam Smith.

The political-economic initiative by Carey and his friends, outlined below, was in large measure responsible for the world’s astonishing technological development in the late nineteenth century. The fight for this development policy and against British “free trade” frames the true, little known history of all the great nations involved in the present political showdown, a century later.

This report has drawn upon manuscript collections and other archival sources which are readily available to historians, but which have been treated as politically untouchable during the reign of the Anglo-American “special relationship.”

Let us now revisit and take inspiration from our predecessors’ work, which we are called upon to resume.

President Abraham Lincoln was shot on April 14, 1865, just as the Union was securing victory in the Civil War. Despite his murder, Lincoln’s cherished program of government-sponsored infrastructure, education and science, his protection for industry and family farmers, continued and blossomed in the nurturing hands of the “Whig” nationalists, headquartered in Philadelphia. Lincoln had been one of them, himself a lifelong champion of the American System of political economy that opposed the British free-trade system. Lincoln’s transcontinental railway to the California coast was completed in 1869, at a Federal government cost of $64 million and huge grants of land. The second Lincoln-authorized transcontinental rail line, the Northern Pacific to Washington state, immediately went into full construction.

With the power of a fully mobilized economy and the world’s most effective military behind them, the American nationalists envisioned technological and political progress in Eurasia that could in effect secure and extend the Union victory. The first steps toward the “land-bridge” focussed on Russia and Japan.

It was proposed that Russian Tsar Alexander II, Lincoln’s Civil War ally, should, with U.S. help, “construct a grand trunk railway from the Baltic to the Sea of Okhotsk [Pacific] of like gauge with our Pacific Central. ” U.S. Gen. Joshua T. Owen was speaking at an 1869 send-off dinner given by Henry Carey for the new American ambassador to Russia, Andrew Curtin. “We have discovered that true glory is only to be attained through the performance of great deeds, which tend to advance civilization, [and] develop the material wealth of people,” General Owen continued. By participating in “girdling the globe with a tramway of iron,” Russia itself would be strengthened and unified. The general spoke bluntly: The allies could “outflank the movement made by France and England, for predominance in the East through the Suez Canal; and America and Russia, can dictate peace to the world.”

Henry Carey had for many years personally managed America’s pro-Russian policy; his widely circulated newspaper columns had turned U.S. public opinion toward Russia during the 1854-55 Crimean War against Britain and France. Among Carey’s invited dinner guests paying tribute to Ambassador Curtin (the former Pennsylvania governor), were the Russian legation, and America’s premier railroad and locomotive builders, along with their Philadelphia banker, Jay Cooke. Over the next few years, contracts were signed, under the supervision of the Carey political machine, for the sale of Philadelphia locomotives to Russia.

Meanwhile, in the 1868 Meiji Restoration in Japan, revolutionaries under Prince Tomomi Iwakura overthrew the feudal Tokugawa warlords; they set up a modem central government guided by Japanese students of Henry Carey.

The world at that time knew Carey as the leader of nationalist political thought, who had been the economic mentor to Abraham Lincoln and to the Union’s industrial strategy. As Kathy Wolfe has reported (EIR, Jan. 3,1992), Japan’s consuls in Washington and New York, Arinori Mori and Tetsunosuke Tomita, worked closely with Carey. Tomita commissioned the first Japanese translations of Carey’s works. Mori would return to Japan to form the Meiroku (Sixth Year of Meiji) Society, dedicated to “American System ” economics, as opposed to British free trade; this Careyite grouping would spearhead Japanese industrial development.

In 1871, Carey’s student and political agent E. Peshine Smith was appointed economic adviser to the Meiji emperor. Other Carey associates were also then in Japan, working with the new government identifying mineral resources, planning transport, and outlining protectionist tariff strategies. On March 15, 1872, representatives of the new Japanese government arrived in Philadelphia, having travelled from Japan’s embassy in Washington under escort by U.S. Gen. William Painter.

The city fathers published the official Diary of the Japanese Visit to Philadelphia in 1872 immediately afterwards, boldly contrasting American and British purposes in the world. The pamphlet described the visit as “an event of great importance … to the mission on which these pioneers of an advancing state of civilization in their own country were engaged … the development of a country which has hitherto been almost hermetically sealed against the commerce of the world, -for the least concession made to the foreign trader was immediately followed by the presentment of that aggressive policy, that arrogance, and grasping spirit of monopoly which have ever followed the British footfall on foreign soil, -so that, outraged and indignant, the Government of Japan has from time to time rescinded the privileges granted, thus retarding the progress of the mighty work of development, not from choice, but from a feeling of absolute necessity as a means to preserve its national and political autonomy.”

The first stop of the Japanese party was the Baldwin Locomotive Works. There, Japanese planners and engineers inspected engine models, machine tools, foundries, and plans for locomotives that Japan would purchase or build itself with American assistance.

The history student today may imagine himself in the place of those Japanese visitors, by perusing the Baldwin Locomotive Works’ nineteenth-century order books, now in the Smithsonian Institution, Museum of American History Archives Center, in Washington, D.C. There is a complete record for each of the thousands of locomotives ordered from the company, including configuration, materials used, price (in the range of $9,000-$18,000 each), and place of delivery. Baldwin’s shipments to U.S. railways and to Russia, Japan, China, Australia, Mexico, Brazil, etc., were calculated to promote world economic development by Baldwin’s politically motivated controllers.

Baldwin, then emerging as the world’s largest capital goods producer, was just one segment of a conglomerate including the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Franklin Institute for scientific and technological research (in association with the American Philosophical Society and the University of Pennsylvania), the Pennsylvania Steel Company, the William Sellers machine-tool works, and numerous other industrial and mining enterprises, which flourished under the Republican Party’s 50-90% tariffs against British imports, Owned jointly by partners known as the “Philadelphia Interests,” this conglomerate was the heart of America’s power, in the political-military-industrial complex whose guiding light was Henry Carey, Among the Philadelphia partners were J. Edgar Thompson, Andrew Carnegie, William Sellers, Baldwin chief executive Mathew Baird, and Gen. William J. Palmer, a Medal of Honor-winning Civil War cavalry officer who would soon begin building Mexico’s national railways.

The Japanese visitors inspected the American Buttonhole Sewing Machine Company (hosted by its vice-president, Abraham HaIt, who was also Henry Carey’s partner in the Carey family publishing firm); the U.S. Navy Yard, to observe the manufacture of naval armaments; the ultra-modern Sellers machine works; and the William Cramp & Sons shipbuilding company,

During this 1872 visit, Prince Iwakura, Japanese cabinet ministers, and the embassy party (about 30 persons in total) were guests in banker Jay Cooke’s house, while they prepared a treaty with the United States and a loan of $15 million for Japanese development. Cooke was negotiating with Japan for Asian connections with the Philadelphians’ Northern Pacific system, intended as part of a global belt of railways, canals, and shipping operations that was to vastly upgrade the economy and power of many sovereign nations.

Jay Cooke’s banking house was vital to the nationalists’ efforts in that era (see EIR, Feb. 9, 1996, ‘The ‘Philadelphia Interests’: The World After Lincoln”). Cooke had been the U.S. government’s principal private banker since the Civil War. He had sold over a billion dollars of small denomination government bonds to the public, to outflank the extortion practiced against the Union cause by London and Wall Street bankers.

Baron Friedrich von Gerolt, the German ambassador to the United States, joined Cooke, the Philadelphia Interests, and the U,S. government in financing and promoting the Northern Pacific railroad construction westward, toward its Asia/Pacific rendezvous. Cooke quietly negotiated agreements aiming at U.S. annexation of the western half of British Canada.

As the Northern Pacific completed its link from the Great Lakes to the Missouri River in the Dakota Territory, the railroad created a terminus city on the Missouri River and named it “Bismarck,” in honor of the German chancellor; Bismarck has remained the capital of North Dakota.

Carey versus London: ‘The Queen pushes dope’

The British Empire viewed this American world leadership as gravely threatening, and in 1873, the British struck with fury.

London Times financial editor H.B. Sampson, his “intimate house guest,” Philadelphia Ledger editor George Childs, and the Ledger’s owners at the British-allied Drexel-Morgan bank, concocted a series of libels against the solvency and honesty of Jay Cooke and the Northern Pacific Railroad, and against their fundraising in Germany, “predicting” an anti-Cooke panic. These slanders were reprinted as leaflets, and distributed in banking circles in the United States and Europe. British bankers froze Cooke out of the money markets, and the Barings and Rothschilds talked down the value of the U.S. government bonds that Cooke was then marketing.

A scandal was gotten up against the Union Pacific railroad, pivoting around Credit Mobilier executive Francis R. Train, of the notorious British intelligence Train family. Congressional hearings smeared the chief political friends of the railroad builders. The demoralized, frightened Congress suspended payment on the old Union Pacific bonds, and thus undercut the market for all railroad securities. Congress then refused any subsidies for the cash-strapped Northern Pacific.

In September 1873, under increasing pressure from international bankers, the Cooke banking house was forced to shut its doors. This set off a panic, closing the New York Stock Exchange for seven days, and closing factories, shops, and mines throughout the country. Northern Pacific railroad construction was suspended for six years. London’s Drexel-Morgan (later House of Morgan) and Rothschild banks replaced the ruined Jay Cooke as the principal bankers handling the bonds of the U.S. government.

There was at this time (1873) a worldwide depression of commerce, industry, and employment, with great historical consequences, as we shall see.

The gravely weakened American nationalists determined to proceed as best they could, in the face of this British sabotage. Henry Carey was then 80 years of age; but, rather than capitulate to feudal oligarchs and their power, Carey fought back with a series of global initiatives that would transform and uplift humanity. Over the next months and years, Carey and his followers worked toward sweeping political and economic objectives in Europe, Asia, and Ibero-America: world industrialization, the defense of labor, and the defeat of the British Empire.

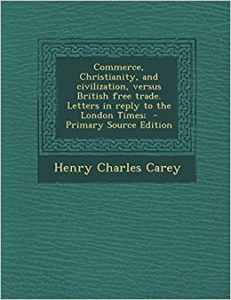

Henry Carey’s 1876 pamphlet, “Commerce, Christianity and Civilization Versus British Free Trade: Letters in Reply to the London Times,” quickly circulated and eagerly received overseas, was a clarion call for the world development fight. Carey singled out the British monarchy’s destruction of China with opium as the chief crime of the age.

The pamphlet consisted of open letters from Carey to the London Times, replying to its editorial of Jan. 22, 1876. The Times had complained that the viewpoint of “Mr. Carey, of Philadelphia, the redoubtable champion of the protective system in the United States,” has been “repeated in hundreds of magazines and newspapers, and forming the staple of endless orations, has affected the economical policy of the Union up to the present time, and is held by multitudes…. ”

The Times warned that free trade, “the cardinal doctrine of English political economy, … to question which must indicate ignorance or imbecility,” is rejected by the Americans, by the French, and even by “heretical” Canadians, who are immigrant “Englishmen and Scotchmen who have grown up in our Free Trade pale, and have been taught to believe that the exploded doctrine,” protection of home industry, “could not be honestly held by an intelligent person.”

In the pamphlet, Carey asks the British rulers to look at themselves as others see them, as pirates and mass killers. These lines from Robert Bums serve as the dedication on the pamphlet’s cover page:

Oh wad some power the giftie gie us

To see oursel’s as others see us!

It wad frae monie a blunder free us

And foolish notion.

The pamphlet is most striking for its attack on Britain’s policy of destroying China with opium.

“Early in the free-trade crusade,” Carey writes, “it was announced in Parliament that the smuggler was to be regarded as ‘the great reformer of the age,’ and from that hour to the present … Gibraltar, Malta, Nova Scotia, Canada, and other possessions [have] been chiefly valued for the facilities they have afforded for setting at defiance the laws of the nations with which Britain has professed to be at peace.” Carey devotes the bulk of the pamphlet to describing how this British “great reformer” has done his criminal work in East Asia. He writes that the East India Company’s opium smuggling into China, practiced with “bribery, fraud, perjury, and violence,” grew to huge proportions before the English monarch renewed the company’s charter with the “express understanding … that opium-smuggling should not … be interfered with …. ”

“Thus sanctioned by the royal head of the English Church,” the dope trade was aggressively expanded. The Chinese “emperor’s councillors [advised] him to sanction domestic cultivation of the [opium] poppy,” and thus stop a demand that was draining the country of all [its] silver . . .. ” Carey gives the emperor’s memorable reply: He may not have the power to stop Britain’s “introduction of the flowing poison . . . but nothing will induce me to derive a revenue from the vice and misery of my people” (emphasis in the original). “So much,” writes Carey, mocking the British Empire’s religious pretense, “for a ‘barbarian’ sovereign for the conversion of whose unenlightened subjects to the pure doctrines of Christianity so much anxiety is felt by many of those eminent Britons [who lobby] . . . in behalf of the ‘ great reformer of the age’ … on the shores of the China seas or on those of the United States.”

Carey recounts Britain’s bloody “bombardment of Canton … [compelling] the poor Chinese to pay $21,000,000 for having been [forced] to submit to the humiliation of being plundered and maltreated by the ‘great reformer’; and . . . to cede Hong Kong, at the mouth of the Canton River, to the end that it might be used as a smuggling depot throughout the future.”

Carey tells of Britain’s unprovoked war of 1857, which forced China to legitimize the annual import of “millions of pounds, of a commodity that in Britain itself was treated as a poison whose sale was … subjected to close restriction.” China was then “thrown open to the incursions of British agents and travellers” who showed “an insolence … [d]etestation, contempt, ferocity, and vengeance” toward Asians, which seemed not “reconcilable with the hypothesis that Christianity had come into the world.”

Carey describes the downfall of India, from its relatively prosperous state before British occupation, to devastation and hunger under Britain’s “work of annihilation”: the forced closing of native Indian cotton manufacture, 70-80% taxes imposed on peasants, the diversion from the production of food and cloth, to the cultivation of opium with which to enslave China.

Britain’s hypocrisy is exposed: “Loud and frequent…have been the [London Times’s praise] of the [British] government … in endeavoring wholly to suppress the little remaining slave trade of Eastern Africa.” But Carey calls attention to the slavery “developed in Eastern Asia, … by Englishmen “:

“There is no slavery on earth to be compared with the bondage into which opium casts its victim,” destroying the body, demolishing the nerves and the free will, reducing man to brute.

Carey quotes from missionaries in China: that “Christian … Great Britain to a large extent supplies the China market with opium, is constantly urged as a plausible and patent objection to Christianity.” The bishop of Victoria (Hongkong) is quoted, showing more candor than today’s lying Christian Solidarity International: “I have been again and again stopped while preaching, with the question, ‘Are you an Englishman? Is not that the country that opium comes from? Go back and stop it, and then we will talk about Christianity.’ ”

Carey describes the descent of England itself into impoverished barbarism for the working population, and idle boredom for super-wealthy aristocrats, reminiscent of ancient Rome and America’s southern slave states.

He surveys the world: the Turkish Empire, the Spanish American nations, India, all ruined and looted after being forced to submit to British free-trade policy. Yet Germany, France, and even Australia (defying mother Britain), have moved toward self-sufficiency, insofar as they have deliberately developed their home industry.

The United States, Carey concludes, has overthrown Negro slavery, so it has escaped from “British free-trade despotism,” under which the slave South and the free North had exchanges “only through the port of Liverpool , which thus was constituted the great hub of American commerce.”

Now America, looking “in a contrary direction,” has effected “a growth of internal commerce that places the country fully on a par with any other nation of the world.”

The battle for Germany

The issuance of Carey’s 1876 pamphlet intersected a decisive political contest in the heart of Europe between adherents of the British and American political outlooks. Carey and his nationalist circle, on both sides of the Atlantic, sought to shift Germany’s course toward government patronage of industrial progress, and into an implicit strategic alliance with the United States. Success would depend on overcoming Germany’s dangerous political and religious fractures.

From about 1 860 up through the 1 870-7 1 consolidation of the German Empire, Germany had wandered away from the direction given the nation by Friedrich List ( 1 789-1 846). List had been an organizer of America’s Whig nationalism, in partnership with Henry Carey’s father Mathew Carey, and Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams. List had returned from Pennsylvania to his native Germany, to create the Zollverein (protective tariff union) and plan the railroads, making List the father of German national unity.

But Prussia had given in to free trade under the hegemony of the Anglo-French alliance and the London-Paris “Cobden” treaty of 1860. Speculation, fraud, and looting expanded until a financial collapse devastated Germany in 1873, coincident with the British-induced collapse of Jay Cooke’s banking house in America.

Socialists told German workers that industrialists were to blame for their unemployment. And Chancellor Bismarckthe victim of a British “sucker game”-was further dividing Germany with the Kulturkampf, his political war against the Roman Catholic Church, the enforcement of restrictions against Catholic religious and educational activities, and the demand that Rome not control the German Church. Against this disastrous drift, the nationalists worked to fundamentally reorient German national policy. Closely coordinating with Henry Carey and his Philadelphia circle (and, beginning in 1878, with the aid of the new pope, Leo XIII), the Germans succeeded in shaping a decisive new course of action. The British-dictated free-trade policy was dropped, and the German government supervised a vast industrial and technological development program. For the remainder of the century, America and Germany were the twin motors of universal progress.

We will now examine the international collaboration that led to this great advancement. It should be of rather urgent interest today, for our befuddled statesmen, to see how the leaders of 120 years ago were extricated from self-defeating policies, from unnecessary economic depression, and from the trap of a “north versus south” clash of religions.

As we examine the actions and strategy of the Carey circle, we must see the republican-nationalist United States as the nineteenth-century civilized world saw it. Having survived the Civil War, the British-instigated slaveowners’ rebellion, America was the pivot of mankind’s hopes against the British Empire and reaction.

Two hundred and fifty members of the Prussian Chamber of Deputies had signed an address to the American ambassador, in response to Lincoln’s assassination in 1865: “You are aware that Germany has looked with pride and joy on the thousands of her sons who in this struggle have placed themselves so resolutely on the side of law and right. You have seen with what pleasure the victories of the Union have been hailed, and how confident the faith in the final triumph of the great cause and the restoration of the Union in all its greatness has ever been, even in the midst of calamity.”

Deputy William Lowe had said of Lincoln, in the Prussian Chamber, “In the deepest reverence I bow my head before his modest greatness, and I think it is especially agreeable to the spirit of our own nation, with its deep inner life and admiration of self-sacrificing devotion and effort after the ideal, to pay the tribute of veneration to such greatness, exalted as it is by simplicity and modesty.”

(These tributes to Lincoln may be usefully contrasted to the attitude of the London Times, which had reacted to Lincoln’s announced decision to free the slaves with editorials on Oct. 6, 7, and 14, 1862, denouncing Lincoln as a “violent zealot” who “will appeal to the black blood of the African” and “excite the negroes … to murder the families of their masters …. “)

Lowe and other German nationalists would come to the fore a decade later, in the German economic crisis and policy conjuncture.

German historian Lothar Galli writes that in 1875, Chancellor Bismarck invited “the [political] parties … to state their wishes and make their offers … principally as regards the violently controversial area of future economic policy, where the Chancellor had very deliberately left all his options open … .

“The first to respond were not in fact representatives of the parties. They were the spokesmen of the protectionist interests . . .. In conversation with Baron von Stumm-Halberg and Wilhelm von Kardorff, both of whom were [legislative] deputies … but figured here purely in their capacity as representatives of associations, [Bismarck] advised them in December 1875 to remain on the offensive and to feel free to attack the free trade policies of the government. Furthermore, he added, the chances were that they would soon begin to find increased support among agrarian interests as well; in this quarter, too, highly critical voices were already beginning to be raised against the policy of free trade.”

Following this December 1875 discussion of Bismarck with Kardorff and his colleague, the tempo of political change picked up dramatically.

But who were these policy advisers, identified as representatives of “protectionist associations”? Utilizing the still unpublished manuscripts mouldering among the Henry Carey papers at the Pennsylvania Historical Society, we are enabled to get a better glimpse behind the events of the great policy shift.

On Feb. 12, 1876, a German journalist named Stopel wrote to Henry Carey, describing the circulation of some of Carey’s writings, edited and issued by Baron Kardorff, a German follower of Carey’s.

About three days later, the Central Association of German Industrialists (or “Central Verband”) was founded in Berlin, as an umbrella organization for the protectionist point of view in German trade and industry. About a week afterwards, 011 Feb. 22, 1876, the Confederation of Fiscal and Economic Reformers was founded among the landlords and farmers, to promote protectionist measures in agriculture.

A certain Herr Grothe reported from Berlin in a letter dated March 26, 1876, to Henry Carey: ” … The protective movement in Germany has very enlarged [sic]. To my Central Verband assist now the greatest majority of industries in Germany and a part of agriculturalists …. In the Reichstag we have now formed a fraction for protecting industries . .. I tell you the names: Dr. Lowe; von Kardorf[f]; Comte Bethusy-Huc; Baron of Schorlemer-Alst; Baron and ex-minister of Varnbiiler; Dr. Grothe; Dr. Hammaiher; ex-minister Windft]horst; Dr. Buhl ; Ackermann; Dr. Thilenius; Fiiustle; Prof. FrUhauf; von Borkum Solfs ….

“The Protectionists have about 140 friends of the Reichstag, the free-traders about 80-100 Members; about 200 Mem” bers are neutral and opportunists. Our ministers are not radical free traders; [to the] contrary it is possible that all Ministers were now elected from the protectionist party.”

On May 15, 1876, Baron Kardorff wrote to Carey, describing the rapid progress of the Carey circle in Germany, including their success in procuring Bismarck’s dismissal of Trade Minister Rudolf von Delbruck:

“Dear Sir !

“Returning from a meeting of a union of gentlemen of the protective party at Leipzig to my parliamentary duties, I was rejoiced by the ‘Letters to the London Times’ [which Carey had just published in the United States] and the portrait you were so kind to send me. Wishing to give the full knowledge and use of your brilliant little pamphlet to my own countrymen, I began on the spot the translation of the letters, with the intention of publishing it in a separate little volume with a preface written by myself in reference to the ideas about the necessity of self defense against the theories and the agitation. of the radical Manchester free trade men, I wish to impress upon my people.

“The day before yesterday I see in the Mercur, a weekly journal published by my friend Dr. Stope I at Frankfurt that he also has begun to translate the letters. But, on the whole I· think my own translation is a better one and notwithstanding the competition of my friend I shall publish it in the above mentioned shape.

“I would not have done it without your own permission if time was not pressing. But our government is bound, to give. warning for the revision of our commercial treaties with Italy, France, Great Britain, Belgium, etc. at the date of the first of July-and I hope that the necessary changes in these treaties will be influenced by the rigor and clearness of your exhibit of the workings of the British free trade policy in the whole world.

“Therefore pray excuse the proceeding of your humble follower as justified by extraordinary circumstances.

“We have had a great triumph, Mr Delbruck, a vehement free trade man and till now chief of the trade department of the German empire, having been induced to take his leave; but the battle is not yet won, the daily journals nearly all writing in obedience to the instructions of the Cobden Club [British free-trade society with honorary members among Anglophiles in America and Germany], and public opinion vacillating between the two sides of the question.”

Despite bitter opposition from free traders, Germany successfully revised its fundamental tariff policy, with a new German protectionist duty on iron, steel, and other products, adopted in July 1879. As a result, smelting and machine works enterprises increased 30%, and employment went up 40%, with higher wages, over the next six years alone.

Beyond the protective tariff, Germany adopted a thorough dirigism. Industries were cartelized for greater productivity, as in the pooling of laboratory facilities. Large banks, interlocking with the state-sponsored cartels, were set into motion for the financing of national and international development programs. The government intensified its sponsorship of education, and constructed a vast network of railroads, canals, and ports; subsidized merchant ships; and built a world-class navy.

Other aspects of the great shift in German affairs under Bismarck-the pro-labor social welfare laws, the German-U.S. partnership for German and worldwide electrification, the turnabout in relation to the Catholic Church-would have tremendous worldwide consequences. We must look further, behind the scenes in America, and into the realms of labor radicalism and Catholic Church politics, to understand these developments.

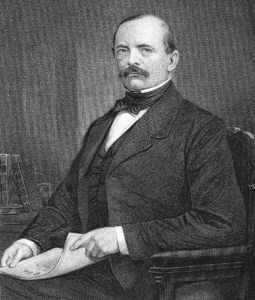

Otto von Bismarck

Recent Comments